Introduction

Plastic pollution is a critical global issue, causing lasting damage to the environment, biodiversity and human health. Despite rising public awareness and increasing regulations, plastic waste keeps piling up. The highly anticipated Global Plastics Treaty, expected to be finalised by the end of 2024, carries high hopes as it will be the first attempt at forming a global legally binding instrument to address plastic pollution across its entire lifecycle. However, there are justified fears that the agreement may fall short of expectations due to diverging economic and political interests across nations. Tackling the problem of plastic pollution will be a long, bumpy road requiring international cooperation, stringent policies and significant financial investment to drive effective solutions.

A critical juncture

The versatility, durability and cost-effectiveness of plastic have revolutionised people’s lives, bringing countless benefits to society. However, once celebrated as the future of modern society, plastic is now one of its most important challenges. Plastic pollution is pervasive. Microplastics contaminate the water we drink, the air we breathe and the food we eat while larger plastic debris cause physical harm to wildlife and disrupts natural habitats.

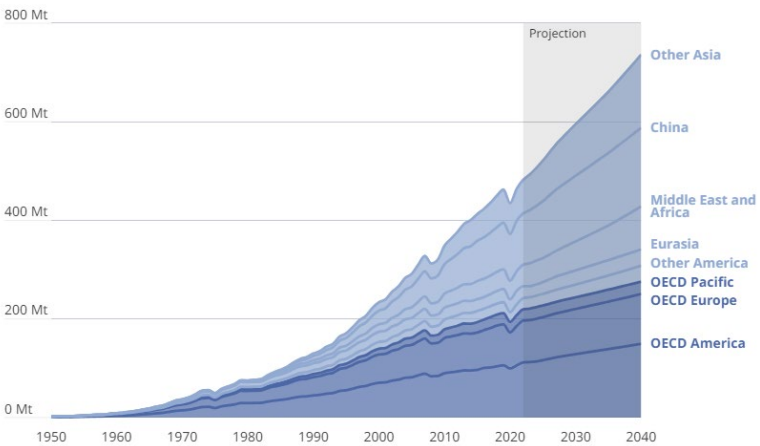

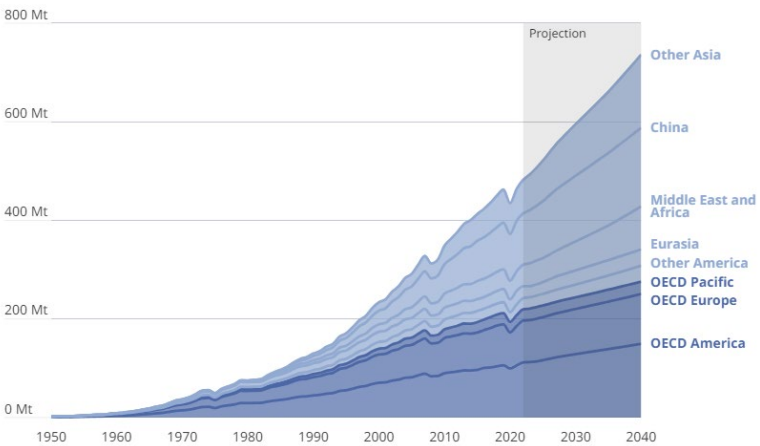

We are at a critical juncture in the battle against plastic pollution. On one hand, society’s reliance on plastic remains high, and currently, we are unable to reduce our dependence. Plastic production has never been higher and, according to an OECD report[1] published in October 2024, is projected to continue to surge by 70% to 736 million tonnes by 2040 if no new policy measures are implemented (Chart 1). The report is explicit: only ambitious global policy action across the plastics lifecycle will be able to end the leakage of plastic waste to the environment by 2040.

Chart 1: Plastic production expected to surge 70% by 2040

Plastics use projections

Million tonnes(Mt), projections from 2022

Source: OECD (2024), “Policy Scenarios for Eliminating Plastic Pollution by 2040”

On the other hand, public awareness of the damage from plastics is rising, and there seems to be a global sense of urgency to address this problem. Countries across the world have been adopting an increasing number of new regulations against single-use plastic and rules to promote recycling and reuse efforts. In Europe, the Packaging Waste and Waste Recycling (PWWR) directive and the Single-Use Plastics Directive (SUPD) have been developed as part of broader efforts to reduce plastic waste and promote a circular economy. China has significantly ramped up its regulatory efforts to tackle plastic pollution, released a five-year plan to cut plastic use by 2025, made circular economy a national priority and banned imported plastic waste. While progress has been made, a shift towards a more circular economy has been complex, and challenges remain. Across South-East Asia, a region particularly affected by plastic pollution, regulations are ramping up too as part of regional and national action plans implemented over the last couple of years.

While these are steps in the right direction, many do not go far enough to truly address the scale of the plastic pollution crisis. Their effectiveness also tends to depend on enforcement, public engagement and development of supportive infrastructure, which currently ranges widely. As time passes and plastic waste keeps piling up, it becomes clearer that individual country-level initiatives are not enough. The OECD is explicit in its recommendations: policy measures need to be implemented at all stages of plastic lifecycle, and international co-operation and resource mobilisation will be essential to overcome technical, economic and governance challenges.

Cooperation is starting, but not without pitfalls

The COP16 summit in Cali, Colombia recently concluded, bringing together 15,000 attendees from 200 countries to tackle biodiversity conservation and implement the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF). The GBF’s 23 targets include eliminating plastic pollution to protect biodiversity. However, the overall sentiment seemed negative[2] after the abrupt end to the conference due to disagreement over the creation of a new global nature fund, highlighting the complexity of aligning diverse political agendas and economic interests.

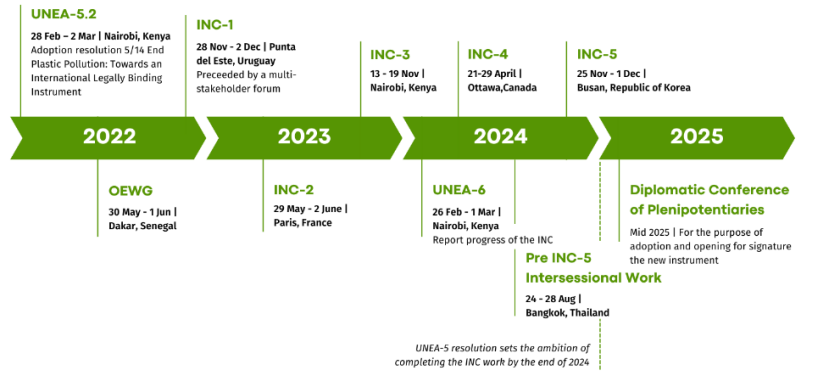

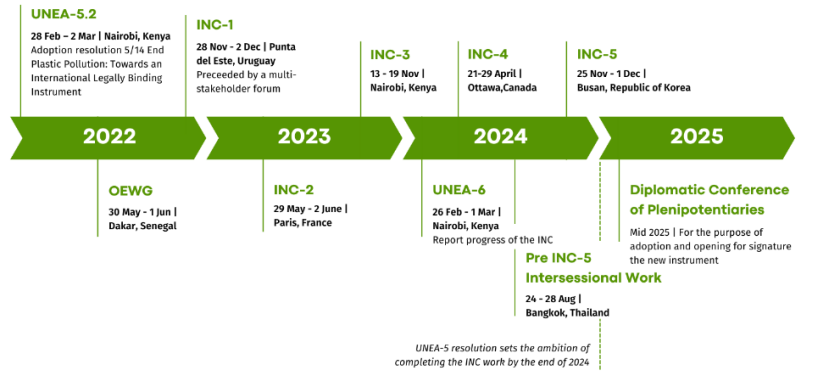

This may be a preview for the upcoming fifth session of Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee (INC-5), taking place in Busan, South Korea from 25 November to 1 December 2024. This highly anticipated session should mark the end of a process started in March 2022 on the back of the adoption of resolution 5/14 by the United Nations Environmental Assembly (UNEA) to develop an international legally binding instrument on plastic pollution, often referred to as the Global Plastics Treaty. For two years, the committee met multiple times (see the timeline in Exhibition 1) to develop this instrument meant to address the full-life cycle of plastic, including its production, design and disposal.

Exhibition 1: Timeline of INC talks to develop a legally binding instrument on plastic pollution

Source: Geneva Environment Network[3]

However, following the fourth session (INC-4), sharp disagreements emerged between the participants, with two main opposing forces developing over the course of the negotiations. On one side, the self-labelled “high ambition coalition”[4] led by 60 countries advocates a cap and phase down of plastic pollution and full lifecycle measures. On the other end, countries and lobby groups that are less interested in limiting production are instead focusing mainly on less contentious downstream efforts[5]. Unfortunately, this approach is akin to refusing to turn off the tap of an overflowing sink, a frequently used analogy[6] for plastic pollution to highlight the importance of dealing with the root of the problem.

These ongoing disagreements are bringing a real sense of emergency to INC-5, with the evident fear of not meeting the high expectations set two years ago. After INC-4, some member States launched the “Bridge to Busan Declaration”[7] emphasising expectations for sustainable production levels of primary plastic polymers. An ad-hoc preparatory meeting was convened in August 2024 to advance technical discussions and build consensus on key issues to ensure a productive INC-5. Early in November 2024, the INC Chair published a third non-paper[8] to try providing a clearer and more concise basis for the negotiation later in the month. During COP16, members of the Business Coalition for a Global Plastics Treaty—which are some of the largest plastic waste producers—also urged governments to come together and establish a bold and effective treaty to combat plastic pollution.

Will the treaty meet the ambitions set out two years prior, or will it fall short of expectations? Looking at recent history, it is hard to be overly optimistic. There is a distinct possibility that we may end up with a watered-down agreement because of parties unwilling to support a full lifecycle approach to reducing plastic waste. We should probably not expect a Global Plastics Treaty to be a solution but rather, at best, the driving force needed to strengthen policy reforms across the globe; or, at the very least, a much-needed wake-up call for everyone. As with any global problem, dealing with plastic pollution is likely to be a long, bumpy and painful road. Collaboration needs to take place at every level, not just among policymakers. This means increased public-private collaboration to shift financing flows[9] but also coordination and efforts in the private sectors, including financial institutions.

Financial sector’s role: engaging public and private sectors, financing solutions

If the world intends to address the issue of plastic pollution effectively, major shifts in plastics-related investments[10] are necessary. This will enable a comprehensive transition across the entire lifecycle of plastics around the world, and financial contributions will have to come from both public and private sectors. According to the OECD, global investment needs for plastic waste management are projected to amount to USD 2.1 trillion between 2020 and 2040.

As we navigate this critical juncture in addressing plastic pollution, the financial sector has an important role to play by initiating the following steps:

- Supporting ambitious policies: Investors should support and encourage stringent policy at regional and global levels. While overwhelming regulations can sometimes be seen as an unnecessary burden, voluntary measures have proven insufficient and are unlikely to be effective enough to end plastic pollution, as these investments are often riskier and the alternatives to virgin plastics more expensive[11]. Having transparent and actionable rules and regulation can create a level playing field for market participants and support the redirection of flows towards projects and solutions that address plastic pollution.

- Engaging with investees: Companies that are well-positioned to navigate and capitalise on the increasing regulatory burdens hold significant value. By actively monitoring and engaging with our investee companies, we can encourage the reduction of plastic footprints and innovation in product design and packaging, among other areas. This engagement could also involve collaborating with other investors to raise expectations, similar to our support in 2023 of the investor statement on plastic pollution[12].

- Financing solutions: Investors can play a transformative role in financing solutions to plastic pollution. Green bonds, for example, can serve as an effective financial instrument for raising capital dedicated to clearly earmarked environmental projects. These projects include the development of biodegradable materials, the expansion of recycling infrastructure and the cleanup of plastic waste from oceans and waterways. An example is the water bonds issued by the NWB Bank to provide loans to the Dutch water authorities, so they can finance projects to remove bioplastic through water treatment and produce innovative substitutes for plastic from waste, among others.

Beyond these examples, the reality is that financial institutions, policymakers, businesses and individuals must all contribute to a multifaceted approach that includes reducing plastic production, improving waste management and fostering innovation in sustainable materials. The fight against plastic pollution is complex and fraught with challenges. While there have been significant strides in policy and public awareness, the path forward requires sustained effort but also realistic expectations. The road is likely to be long and difficult, but only persistent effort and collaboration can move the needle forward.